Mind, Body & Bike – James Hibbard & Freedom Matters

On the arts of cycling and philosophy

James Hamilton Hibbard is a Northern California-based writer and former professional cyclist who studied philosophy at PhD-level.

His philosophical memoir, THE ART OF CYCLING: Philosophy, Meaning, and a Life on Two Wheels, explores questions of embodiment and meaning in our increasingly detached and virtual society, and was shortlisted for The Sunday Times 2022 British Sports Book of the Year, Cycling.

In this conversation we discuss:

- His journey as a professional athlete

- His views on the history of philosophy and the guidance that it brings

- How his experience cycling has helped him to understand philosophy better

- How elite sport prepares you for life

This is a conversation for our summer of joy series, designed to bring you fresh perspectives and inspiration on ways to live life differently.

Host and Producer: Georgie Powell Sentient Digital

Music and audio production: Toccare Philip Amalong

Transcript:

James: I think cycling certainly has helped me, especially now as a long retired athlete to realize how true that sort of verdict is: that you’re far more than your rational thinking self. And there are many things that are not only not rational but can’t even be articulated or captured in language. And in fact, those tend to be, for me at least, some of the most important things about what it is to be alive.

Georgie: Welcome to Freedom Matters, where we explore the intersection of technology, productivity, and digital well-being. I’m your host, Georgie Powell. And each week, we’ll be talking to experts in productivity and digital wellness. We’ll be sharing their experiences on how to take back control of technology. We hope you leave feeling inspired, so let’s get to it.

This week, we speak with James Hibbard. James is a former professional cyclist who competed both on the road and in the Velodrome, at the junior elite and national levels. His book ’The Art of Cycling’, is a meditative love letter to cycling, which is written on the foundations of philosophy, James’s other great interest.

The book covers the history of thought through the lens of cycling, breathing a fresh perspective on life and challenging us all to move away from the abstract, detached, and virtual worlds which we so frequently occupy. We discuss how through his experience as a professional athlete, James came to know firsthand why embodiment is vital, and how we are so much more than our thoughts.

This is a conversation for our summer of joy series, designed to bring you fresh perspectives and inspiration on ways to live life differently. We hope you enjoy it.

James, thanks so much for joining us for the Freedom Matters podcast. It’s really fantastic to speak with you today.

James: Thank you so much for having me, Georgie. I very much appreciate it. I’m really looking forward to speaking.

Georgie: Amazing. So, we are talking now about your love affair with cycling and all of our love affairs with cycling. There are lots of people in Freedom that really love time on the bike. And I think I’d just like to start there just to hear a little bit about your journey with cycling and what it really means to you.

James: Yeah. So, I want to first of all contextualize both my background and the book. I had a good domestic pro cycling career, but certainly nothing special. And in terms of cycling biographies or anything like that, there are certainly other cyclists’ biographies that can explain life at the Tour de France and the life of a pro far better and more intimately than I’m able to.

But what I wanted very much to do was to tap into my love for the sport, to tell deeper stories about what it means to be committed to something, the sort of psychological costs of being committed to something, and to shed light on how you can better understand yourself through the process of working very hard to develop a particular tangible skill.

In terms of my getting started in the sport, I live near the Hellyer Park Velodrome near San Jose, California. I grew up only about 10 minutes from it, which is not so rare to be that proximate to a velodrome when you’re in Britain or certainly the EU. But there’s very few functioning velodromes with racing programs in the US.

Whether it was weekly racing on Wednesday nights, Friday nights, district championships, or things like this. I was a cross country runner in middle school, 10-12 years old. And we had a family friend who took me to the Velodrome for a Friday night race. And I was able to see it and was just enamored by the sort of spectacle of the whole thing.

It was super contained, which I liked, was under lights, and there were spectators. And it seemed this sort of magical theater where you could be super aggressive. And that was okay. I played team sports and was not particularly good. The sort of cliches about cyclists with poor hand-eye coordination were true for me.

Georgie: Along with rowers.

James: Yes. I was going nowhere for ball sports. Now it’s apparent. But my initial fascination with running was this just seemed like a contest of who could suffer the most. And it seemed as if sort of people would give up. Witnessed running the mile when I was 10 years old and you look and it didn’t seem like a purely physical thing, but people made a conscious decision to give up at some point. And it struck me as interesting to try and not give up in the sort of contests of suffering.

So, getting back to the Velodrome at Hellyer Park, I was just transfixed seeing Friday night racing there. You were able to repeat things and I could see, that you could figure out where your mistakes took place and not repeat them, which I innately found appealing.

And then also the equipment. I think that any cyclist that doesn’t fall in love with equipment would stick with running. There’s something just, to me, that was always very elegant about a particular track bike. So, direct drive, so no derailleurs, no brakes, and typically high-end competitors will have a disc wheel in the rear. So, it just looked aerodynamic and exotic in a way that appealed to me.

So, it was really this sort of initial exposure to racing on a velodrome that got me interested in the sport, more so than the sort of typical story of watching the Tour de France or anything like that. And certainly, I later was exposed to all of that, but it was this initial trip to the Velodrome at a pretty young age that got me started.

Georgie: So, cool. This is an aside, I’ve been trying to work out for the Commonwealth Games this summer, whether or not I can get my daughters up to go and watch. Because British Cycling we’re starting to do really well, especially in the Velodrome and I think it would just be fantastic for them to see it. There’s something very gladiatorial about it. I think that’s quite interesting. That’s really ancient in terms of watching a real-life fight in action.

James: It depends upon the event. But an event like the match Sprint on the Velodrome, it’s one rider against the other and it’s exceptionally gladiatorial. You get riders who you’re literally lined up at the track, they’re eyeing one another, and there is this very sort of gladiatorial sense to it.

And even going back to what I was alluding to it was, I’m sure I probably in the book, inadvertently revealed a whole lot about my background, but middle-class Northern California, born and bred. And there was definitely a sense of this gladiatorial element and being this aggressive is forbidden in a lot of other walks of life, except it’s rewarded in this one.

So, certainly, I remember being 14 or 15, and racing, a match Sprint or a Kieran and it just being massively aggressive. Riders, at times, literally crashing one another, it just being very physical in a way that I liked at the time. Certainly, some of that sort of teenage testosterone-driven bravado has abated.

And now I look back and I’m like, question why some of it seems so compelling to be totally candid. But at the time, that gladiatorial element about the track was hugely appealing to me.

Georgie: And related to that, you made that observation that it was basically a kind of test of suffering. And that was also something you were very much up for.

James: Was very much up for it. And it seemed every time I approached my own physical limits, which as I said, I had some physical talent, for sure, but was endowed with some massive amounts of physical talent.

And I think whenever I approached my own physical limits, my own limits of suffering, it struck me as a more psychological relenting than a physical one. It always seemed that I shouldn’t be able to go further if only I could push myself.

So, there’s a sort of addictive quality to this, where it felt that if I was simply able to push myself harder, I should be able to do whatever I wanted to my body. And that was a very interesting, addictive, sort of continual experiment.

And I do think that in elite sport, there certainly is this sort of addictive gamblers mentality, where every athlete will have the sense that you’re making progress. And if only I moved my saddle five millimeters, or if only I undertake this new type of threshold interval, everything will be different.

You mentioned British Cycling and its success. And Team Sky, the British professional road team, talks about this idea of marginal gains. So, looking through 30 different elements to human physical performance, and trying to buy a 10th of a percent here, a quarter of a percent there to add up to something that cumulatively has a huge impact upon performance.

So, I think that marginal gains idea is a very old one, in fact, in sport, and what drives athletes from year to year. You say I didn’t have the best of seasons, but next year, X, Y, Z sort of changes are going to allow everything to cumulatively be different.

And more often than not, that’s not the case. And I would frankly question any elite-level athlete that has some sort of major epiphany breakthrough. But nonetheless, it speaks to this sort of, I think, addictive aspect of a lot of elite level athletes.

Georgie: Chasing, chasing. So, tell me quickly, I want to get back to the whole thesis of your book and the link to philosophy in cycling. But before that, can you just quickly summarize what happened with your career so our listeners understand where you went with cycling in the end?

James: Absolutely. I started, as I mentioned, very young. I think in retrospect, probably too young. I was the sort of typical progression of being the California junior champion. I was then a medalist at the junior national championships, which got me a spot on the junior national track team.

While still in high school, I moved out to the US and Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, and also spent a lot of time at the training center in Chula Vista, California and transitioned to being on the senior national sprint team. I raced internationally for the US and the southern games and Trinidad and Tobago, which is at least in the Western Hemisphere, a pretty big event and made the podium there.

I then raced for two professional road teams, but frankly, by my mid early 20s, my last year racing on Team Health Net, my health was not so great. I was overtrained, I was burned out, and I’d been doing it for frankly too long at too high a level and just was utterly physically shot.

I had Epstein Barr Virus and a lot of other sort of cumulative problems from simply having trade nearly full-time since I was about 14 years old. So, a good, interesting career but certainly allowed me to travel the world and race internationally and have a lot of amazing experiences.

But also one that I think unfortunate in terms of timing, certainly looking back on those years, essentially active 1999 to about 2005 was, I think some of the worst years that one could choose to be active in terms of doping culture and that happening.

And I’m not close enough to it now to say with any certainty, but I do think that cycling has taken the problem of doping very seriously and addressed it in the last decade where athletes who are coming up, I don’t think, are having to make those sort of choices any longer.

Georgie: And reflecting back, how do you feel now about your career? Are you glad you spent that long on the roads and dedicating your life to cycling?

James: I have mixed feelings still. I think it’s very complicated. I think that there are some parts of it, and certainly some friendships I forged that are absolutely well worth it. And the ability to focus entirely on improving in one very tangible physical realm is something that I don’t regret.

I think that there are other aspects that have been as an adult a little bit more destructive. Whenever I find myself now entering any, let’s call it like, rule-bound game, right? Be it a working situation, entering into now working in writing and publishing, I do find myself exceptionally suspicious of entering into something where the game rules are not what they appear initially. So, I do find myself really, I think unduly sensitive to feeling set up for failure.

Georgie: Because of your experience with doping in cycling or?

James: Yeah, yeah I think so. Because I think the other thing where I was a bit naive at the time, was a very sort of chariots of fire idealized understanding of what sports were meant to be.

And now as an adult, that is woefully naive. Obviously, sports are a commercial enterprise. You’re literally wearing a jersey that served as a billboard for a litany of corporate and industry sponsors, all of that.

But I do think that what was slightly difficult was out of one — one side, this being society cultures, highest, most lauded outlet for something that is pure and meritocratic, and then realizing that was in practice very far from the case.

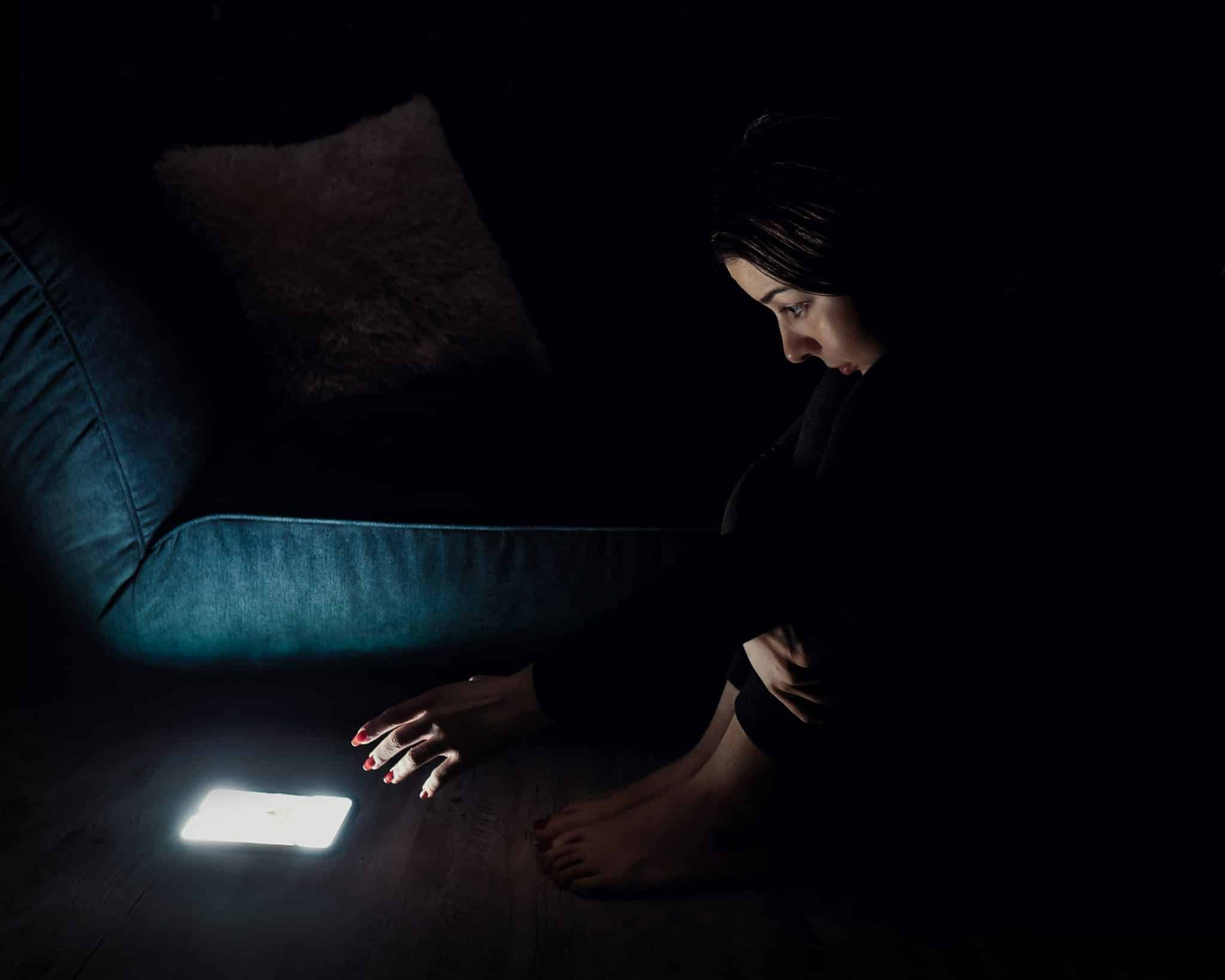

And I think that the very act of cycling itself, of riding a bike now as someone in my 40s has made it very clear to me that the real problem that not just myself, but a lot of people face is one of being distracted and being drawn away from oneself in a sort of constant tug of war as to where your mind is. And concerns about who’s emailed you and who’s going to call you and this sort of constant wheels turning plan making mentality that’s very much rewarded.

And I think that simply being on a bike or playing the violin well or woodworking or any number of very tangible and body tasks, draw you back into the world in a way that’s very much needed now.

Georgie: That is so interesting. And as you say, you start off by saying that you learn so much by leaning into a skill that you become very good at and that you devote so much of your life to.

And for you, it was spending hours and hours on the road. And when we talk, we’ve talked before, I was interested in how you spend your time when you were writing and how your thoughts wandered.

But I think for you, what you’re saying is actually the most important part of those hours is to recognize that you are in your body, and you’re connected to your body, which actually a lot of our daily life removes us from if we’re not careful.

James: Precisely. So, I think that the other aspect to the art of cycling is very much a story of the history of Western philosophy. I think a good sort of person to lay it out, and it’s hopefully not a straw man argument at all, is that of René Descartes, who very famously divides the body and mind.

And when you’re thinking about Descartes, that’s again, you can it’s very easy to say, how is this at all relevant or salient to anyone’s psychological makeup or current situation.

But the truth of the matter is, this whole idea of mind body dualism, as it’s called, is absolutely pervasive, right? We have this idea that we’re all contributing to knowledge, and our mind is elsewhere, perhaps located on the internet, on our phones in the knowledge that we’re producing in our daily work.

So, this whole idea of Descartes, which certainly goes back to ancient Greek philosophy, is, I want to argue, exceptionally relevant to our current situation and the way that all of us walk around perceiving the world.

And I think that, although it’s had a great deal of practical scientific use, in terms of our ability to control the world, it also is a destructive thread that needs to be pushed back against, in order for us to feel happy and comfortable and at home in the world.

Georgie: I was interested, whilst intuitively it doesn’t feel natural, why is living in our heads and not our body so dangerous? How is this dualism playing out in real life?

James: I see it playing out in as much as all of our interactions become virtual or mediated and indirect, in a way that makes everything feel distant and abstract. The idea of abstraction is a destructive one, because of the fact that it’s, I think, more than anything else nonspecific, right. One bit of information can oftentimes be substituted for another.

The word that existentialists use a great deal is alienation. So, this idea of, yes, you’re contributing a bit of knowledge, but you’re fully cognizant that someone else could be equally contributing the same bit of knowledge. There’s nothing particular to you, or your existence about what you’re slotting into, or the conceptual schema that you’re a part of. It’s very much something that can be easily substituted.

The group of existentialists, that I also talk about a great deal. But this group of existentialists, in the 1950s and 60s, predominantly post war Europe, figures like Sartre, Martin Heidegger, this idea of alienation and anxiety.

There’s a reason for all of them in terms of this idea of substituting knowledge and everything being interchangeable. And what that does to one psychological constitution and sort of ability to feel at home in the world.

Georgie: Yeah. And just like in seeing, like a living day experience, how when, you know when you do work on Zoom, and you’re working remotely, and all your interactions are really cerebral with a bit of voice.

James: Right. Right.

Georgie: How there is another layer of vulnerability to that. And when I was actually just saying to Phil today, like, I think he’s the third person that I speak to, like, in my list of people I speak to most in my life at the moment, he’s the third person. But actually, I’ve never met him in person. [crosstalk]

James: Right, right. So, this detachment is so salient. Yes.

Georgie: It is. And you do — I think there’s a vulnerability that comes with that because you don’t really create that same grounding and that same sense of trust and connection with someone until you really have faced up to them.

James: Right. And we’re back to this sort of issue of face-to-face embodiment and a lot of trust and understanding.

During the enlightenment, philosophy was termed nothing less than the queen of the sciences. So, by the mid-20th century, after a little bump in terms of popularity, because of existentialism, in the post-war years, philosophy very much retreated to, okay, how can we sort of clean up language for science and add a higher degree of clarity to verbal discussion and scientific inquiry.

So, philosophy too also really diminishes what it thinks it can do and what it thinks it can explain.

Georgie: I know you do spend a lot of time looking at some of the philosophies that fall down in helping us to understand ourselves and understand our life. But I’m interested in your journey on the bike and then in your journey in writing this book, and in your experience with philosophy over time.

Which philosophies actually do you think have got it right? And what philosophies can we turn to and learn from?

James: I think very much for me, the thinker that stands out in the history of philosophy as being absolutely ahead of his time is Friedrich Nietzsche. Tellingly, he died in the year 1900. So, standing at this precipice of modernity, I think in a very interesting way.

And I think for me, more than anyone else, Nietzsche is able to articulate the sense of spiritual loss that existed in the form of diminishing religious belief. Nietzsche famously pronounced God as dead.

The story is a bit more complicated than that. And if you look at the rest of the Nietzsche extract there, it’s not only God is dead, but he goes on to say, and it’s you and I, who have killed him. So, this whole sense of scientific truth searching, in fact, leads to the death of any sort of viable spiritual outlet.

So, I think for me, the whole idea of philosophy failing to account for a number of things, rational language failing to account for a number of things that are intrinsic to the human experience, is very well articulated by Nietzsche.

Georgie: And if he was alive today, looking at the world that we live in, surrounded by the internet, and connectivity, what do you think he would be saying now?

James: I don’t think that he would be a total Luddite. I think it would be very easy for someone to say that Nietzsche would simply reject all of this and go and live in a cabin in the woods or something.

And I actually don’t think he would. I’m old enough to remember the internet in the late 1990s, and early aughts, and the sort of potential for it to democratize information in a very unique, unprecedented way.

So, I think that Nietzsche would still very much have that sense of hope and possibility for technology and some progress. But I do think that he would also be exceptionally skeptical of the sort of herd mentality, because I think you see that time and time again.

You even see, when you go to Google, this whole idea of the wisdom of the herd, which, of course, is something that Nietzsche would very much dislike. He would not believe that there would be any aggregate understanding that would be better than that of the exceptionally erudite individual. So, I think that would be his biggest cause for concern.

Georgie: It’s interesting that mindfulness is becoming so popular. James is not the only one to recognize that we need to find ways to connect our body and mind. I asked James if he saw this as a positive movement.

James: I think that overall, the cultural sense is very much towards let’s, as you say, illustrated by mindfulness and any number of other practices that sort of draws you back to the immediacy of your breath, to your surroundings. I think where it becomes slightly concerned and skeptical is when tools like mindfulness are immediately positioned as a means of becoming more productive. That’s where I start to become very concerned, because I think that, I don’t know, concerned — skeptical.

Because I think that this whole idea of for most knowledge, workers of productivity and output and things like that is buying into this abstract mentality of, we can go and spend a little time doing this thing, feel a little bit more in touch, and then come back and produce more in this space that ignores the body. And I think that’s a very risky thing to do.

I think one person who also speaks about this in a very articulate way is the German philosopher Martin Heidegger who speaks about this whole idea of care.

So, I think that it’s exceptionally interesting to think through what sort of skills and outputs and means of being productive aren’t rewarded, culturally at the moment. And they’re all very much engaged in the creation of novel conceptual outputs, as opposed to this idea of care. So, you can ask easily, okay, what’s care? That’s a fuzzy thing. I think that you can look at care as caring about another person.

So, in the most literal sense, a caregiver, caring about the development of a skill, so riding a bicycle, or playing a violin. So, you think of economically, and culturally what’s rewarded. It’s abstract, and it’s novel.

So, I think that there’s something that’s immediately raised by what tends to be rewarded economically at the moment and all of those things that really are care-centric. Long-term development, not novel, not abstract, tends to not be rewarded particularly well, relative to hear as a new app, no matter how banal the sort of app might be.

Georgie: You make the point in the book that looking from the outside looking at something like a sport, you could say, it’s actually, it’s completely pointless. Why are you spending all your time learning how to ride a bicycle? What are you going to gain from that? But actually, there’s a lot to be gained from caring about something in the way that you did.

James: So, this whole idea of pointlessness or purpose is, I think, a very interesting one, because this idea of what’s the point of that, both towards sport or towards philosophy are questions that not only have been posed to me, but I’ve asked myself.

So, with philosophy, what is the point of that, trying to understand what someone 2500 years ago said or wrote, what would be the point of that? As opposed to trying to insert myself into a new Silicon Valley venture, which would create something novel?

So, I think that disabusing ourselves to some extent, of very pervasive notions of the only thing that has purpose is new and abstract, is absolutely necessary for psychological health and well-being.

Georgie: Yeah. And the well-being of community as well.

James: Absolutely.

Georgie: So, on that, I’m interested quickly to understand from you how your journeys, both cycling and with philosophy, have helped you to understand who you are.

James: My father also studied philosophy. I remember him when I was in middle school, or perhaps even younger, asked me the question of, for example, of where I thought I lived in my body. So, these were questions that I had been thinking about for a great deal of my life.

And I think for me, the two main takeaways, I would say, are at this point in my life, would be to back away from the cerebral and abstract and to understand that those are incredibly powerful tools, but merely tools. And that I’m not entirely my cerebral, abstract mode of thought. It’s just something that you can slip into when you need to accomplish a given task in life.

And then I think cycling certainly has helped me especially now as a long retired athlete to realize how true that sort of verdict is that you’re far more than your rational thinking self. And there are many things that are not only not rational, but can’t even be articulated or captured in language.

And in fact, those tend to be, for me at least, some of the most important things about what it is to be alive. And that really understanding, and this sounds rather trite, but even honoring those aspects of my own existence that can’t be articulated is hugely important.

Georgie: I think it’s an interesting challenge, actually, to a lot of people who work in our sector, myself included, because there’s an extension of that and we talk a lot in digital well-being about how you are what you pay attention to, your life is what you pay attention to.

And I really like this conversation because I think it’s forcing us as they actually know that it’s really not. There are a whole other layer to being beyond simply where you place your attention that we need to tune back into and reconnect with.

James: And to even broaden the conversation, and I think that one of the most two interesting things that’s taken place and other fields, the social sciences, physics and the hard sciences is the increasing realization that things are not as rational, as predictable as they appear.

[inaudible 00:30:15] conversations have taken place in economics and whenever human behavior is modeled to be completely rational, it turns out to be far from it. And I think that people who are working in tech and writing code, living in the Silicon Valley have a great deal, are certainly intelligent enough to understand that abstractly, but applying it is a different matter.

And applying it to something that is economically a perilous thing to do for a great number of people. And I think it’s your swimming upstream in order to really live in any meaningful way, some of the things that we’ve been talking about. Because they’re not practical and they’re not rewarded.

Georgie: So, unfortunately, we can’t solve the reward problem at the moment. We can’t change society with one podcast episode, but we’ll try. But from a practical perspective, what would you advise our listeners to think about or to do in order to realize there is a lot more to life than their thoughts?

James: I think engaging in something without expecting any results. I think that simply doing for doing sake, is hugely valuable, and avoids these sort of output-driven achievement traps that I think are so pervasive and so dangerous. And can even leave something as immediate and embodied as cycling to become a far more abstract exercise in analysis of power data, or wind tunnel data or something like this.

So, I think that a non-achievement-based attempt at engaging in one’s bodily existence in the world is the most practical advice I can possibly provide.

Georgie: Another practical note, you’re obviously dedicating your life as a writer. A lot of our listeners to the podcasts are also writers. Do you think your training as an athlete and your approach to training has helped you to structure how you think about writing?

James: I think where it’s helped me more than anything else is the amount of rejection one receives as a writer is very akin to starting. And especially in cycling, it’s not a football match, where, at least at the beginning, one has a 50/50 chance of winning. You’re starting typically in a field of 110 riders and your odds are not good, let’s be honest.

So, I think that the sort of feeling of keep trucking in sort of the face of rejection has been the biggest advantage that I think I’ve gained from cycling is just an ability to deal with failure more than anything else. And certainly probably some degree of grind to the south discipline. I definitely don’t believe in any sort of inspiration striking. Inspiration strikes when you sit down and just work day in, day out.

I think that it’s a neophyte idea to think, boy, I’m in a perfect mood. There’s a thunderstorm and I’ve had half a glass of wine and I’m going to go write now is obviously not at all realistic. So, yeah, I think those two things probably just continued work and the ability to handle a great deal of rejection as par for the course.

Georgie: James, you’ve been a fantastic guest. I’ve really enjoyed talking to you today. Thank you so much for your time.

James: Georgie, I very much enjoyed it. Thank you so very much.Georgie: Thank you for joining us on Freedom Matters. If you like what you hear, then subscribe on your favorite platform. And until next time, we wish you happy, healthy, and productive days.