Laziness Does Not Exist – Devon Price & Freedom Matters

Join Dr. Devon Price on Freedom Matters where we discuss laziness as a social construct

What if laziness doesn’t exist? What if it is just a social construct, that is getting in the way of us all living our best lives? In this episode, we welcome Devon Price, the author of the books Laziness Does Not Exist (with Simon & Schuster), and the forthcoming Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity (with Penguin Random House, out next year).

Devon is a social psychologist and clinical assistant professor at Loyola University Chicago. Their work has appeared on CNBC, Huffpo, the Financial Times, Lithub, Jacobin Magazine, and NPR, and they write regularly at Medium.

In this episode we discuss:

- where the concept of laziness first originated and why it persists

- how your productivity is not your worth

- how to live a lazy and more fulfilling life

This episode features the music of Freedom team member Tanajah!

Host and Producer: Georgie Powell

Theme music: Toccare

Transcript:

Devon Price: My life is really a reduction to absurdity of the idea that your worth and your happiness comes from your productivity. Most of my life, up until a few years ago, I was really playing by the rules of that game.

Georgie Powell: Welcome to Freedom Matters, where we explore the intersection of technology, productivity, and digital wellbeing. I’m your host, Georgie Powell. Each week, I’ll be talking to experts in productivity and digital wellness. I’ll be asking them three questions to get to the heart of what productivity means to them.

This week, I’m in conversation with Devon Price. Devon is the author of the books Laziness Does Not Exist, and the forthcoming Unmasking Autism: Discovering The New Faces Of Neurodiversity. They’re a social psychologist and a clinical assistant professor at Loyola University in Chicago, and Devon’s work has appeared on CNBC, HuffPost, and the Financial Times. Today, we’ll be unpacking the concept of laziness, discussing why the construct is unhelpful, and instead, how we should reset our lives to embrace it.

Devon, welcome to the Freedom Matters podcast. Thank you so much for joining us.

Devon: Yes, thank you so much for having me.

Georgie: To kick off, I asked Devon to explain where the concept of laziness originates from, and just why and how it has persisted in our culture for so long.

Devon: Yes, so “Laziness does not exist” is all about what I call the “Laziness lie,” which is just the shorthand for a lot of these implicit, unstated beliefs that we absorb from the culture. The way I write about it, the laziness lie has three major tenets that most of us, on some implicit level, believe.

The first is that your worth is determined by your productivity, the second is that you can’t trust any needs or limitations that you feel in yourself that might be a barrier to that productivity, and the third is that there’s always more that you could be doing. So even if you are higher achieving in work, you could be mentoring more people or taking on more responsibilities or growing in that role, or your home is a mess, or you’re not doing enough for your kids, or you’re not doing enough activism. There’s basically a never-ending litany of things that we can feel inadequate about because we’re all being asked to do too much.

In terms of where it comes from, in the book, I trace it at least as far back as the Puritans, a lot of Christian ideologies that we had from that period about people who worked hard being very virtuous, and that being a sign that they were already saved, and people who were struggling were suffering from sloth, or it was a sign that they were already dammed.

So we’ve had this blame-the-victim-for-their own-struggles logic really deeply ingrained in our culture since at least that period. As someone who’s writing in the US, it became very politically useful around the time of enslavement and then following abolition to really have this belief system that certain people are lazy and need to be basically forced or coerced into working, and that work is the only way of earning a comfortable life for yourself. It’s been exerting really toxic influence on us, on our lives, ever since.

Georgie: Looking around, sometimes I feel like it’s getting worse, these litanies you describe, it’s snowballing. Besides, the concept of toxic productivity is something that’s so embedded now, especially in our work culture. Do you think that is the case? Do you think it’s almost getting worse and harder to step away from?

Devon: I think it’s something that definitely changes its packaging over time, and I think there are a lot of reasons why, right now, it seems particularly impossible. Just on an economic level, we are working more than ever before for functionally a lot less money. That’s certainly true in the United States, and in a lot of countries as well, and we just have less of a support system for people who can’t work or who are struggling.

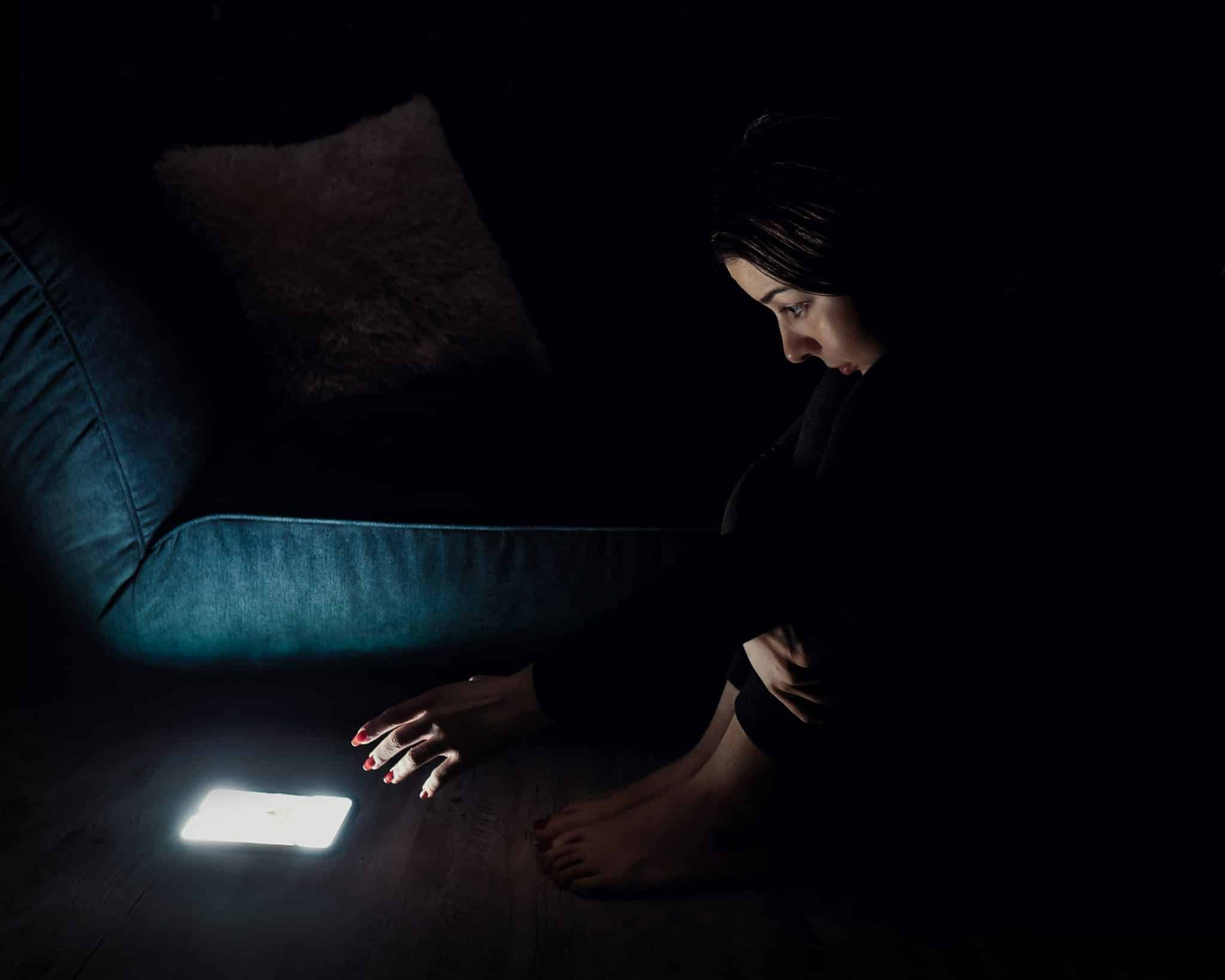

It’s also the case that technology has made it even harder than perhaps ever before to set a boundary between work and life. We have this idea of work-life interference. It is inescapable when you have work on your phone, giving you constant notifications, not just from e-mail anymore, but from Slack and Microsoft Teams, and they didn’t have a social media presence.

Then, the pandemic, meaning that where we worked was also where we lived, no matter what kind of line of work we were in, and it just being so inescapable and feeling so precarious, I think. Because of these economic realities, it just makes it even easier for us to be exploited because we’re so worried that if we don’t jump every time our boss tells us to, that we’re going to be out on the streets.

Georgie: It was interesting to hear Devon mention the role of technology in all this. In their book, they talk about how technology contributes to our sense of busyness, but also how there is a place for technology in supporting our downtime and rest. I asked Devon to explain more.

Devon: Yes, so I will always lord the power that the internet has to help us find people like ourselves and find small communities and creative outlets and give a voice to people who haven’t been heard. I also talked in the book about cyberloafing, which is this very negative term that researchers have for when people goof off online at work.

So the work of a graduate student of mine, Marvin Puente, who really explored how cyberloafing can be restorative and give people a little oasis and a break in the middle of a stressful workday.He’s a Mortician, and his dissertation was studying morticians working during the pandemic, a very busy, really traumatizing time to be working in deathcare. He really found that people like himself were using the internet to just take a little breather and have a little escape and a moment of social connection, or just stimulation in a way that was really healthy for them.

At the same time, the internet has become very much a advertising platform. Almost every social media site is very much designed to get us frustrated and doomscrolling, looking at bad news, and getting into fights because that’s how they keep you refreshing the site and seeing more ads.

A lot of workplaces are very dependent on, as I mentioned, Slack, Teams, keylogging software, employee-monitoring software that really squeezes every last drag of productivity out of us. So it’s very much a double-edged sword. There’s a way that the internet and technology can free us and let us be playful and explore and be creative, and then there’s the way that it’s used to manipulate and drain us.

Georgie: In the book, Devon talks openly about their own personal journey and the wake-up moment that led them to totally change their approach to life. I asked him to share this again for Freedom Matters.

Devon: Yes, my life is really a reduction to absurdity of the idea that your worth and your happiness comes from your productivity. Most of my life, up until a few years ago, I was really playing by the rules of that game. I had lots of extracurriculars in high school, I was taking college classes in high school. I finished college early, went straight to graduate school. I finished graduate school and got my Ph.D. when I was 25, and then I went straight into a postdoc research position.

Right as I went into that postdoc, I was overcome with this intense fever that would hit me every single night, like clockwork, from February of 2014 all the way through to November of that same year. Every single night at six or seven, I would just get 103-degree fever and chills and be just laid out.

Even as that was going on, and I was having all these medical tests to try and figure out what was going on with me, I was still trying to cram as much productivity as I could into those few hours of the day where I was healthy or felt healthy. So I was still working out every day, I’m still working a full-time job, I was still trying to think about applying to academic tenure track jobs.

It was just absurd, and I eventually reached this breaking point where I realized there was no easy medical solution for me. We couldn’t find a particular condition explaining why I had a heart murmur and a fever and all of these issues. I just had to rest and really dramatically cut back and rethink how I was defining my life and who I wanted to be, even. It was only after I did that that my health started to recover.

Ever since then, I’ve just looked at my students differently, I’ve looked at my colleagues differently, and I’ve just seen how this ideology of overwork just really taints so much of our lives.

Georgie: Yes, and we’ll come on to that in a minute because I think it’s a really interesting point about changing your life versus changing this social philosophy that we all live by.

Before this, though, I wanted to ask Devon for some advice. Many of the people listening to this podcast may already feel like they have a healthy relationship with their work, and that they’ve found balance and fulfillment in the way they live their lives. But like me, you may be concerned about others close to you, who are still swirling through a busy, busy life. How, I asked Devon, do we help other people to realize that a life less busy may well be one, which is much more fulfilling?

Devon: It’s so hard and it’s so frustrating to witness. I do talk a little bit in the book about the emotional boundaries of knowing what you can and can’t do for someone else, and I think this is someplace where it comes in there.

In my own life, I’ve been going on this whole journey of really cutting back and deciding, in my case, to get off of the academic treadmill of applying for tenure and doing research and those kinds of things because I could tell that world, in particular, was really wearing me down, and I was just never going to be healthy and happy in it.

At the same time, my partner, he’s an actor, and he works for a bunch of non-profits in education and performance. Those worlds, you’re just fighting for crumbs all the time.

If you have a job in the arts, you’ll work for just pennies, and that you’ll just sacrifice everything in your life and work really long hours for it.

I can’t necessarily make him reach his breaking point any sooner than he’s going to make it, even though my life is such an illustration of it, and he saw me shivering on the couch for months. So I think it’s something where you can set your own best example, and you can try to keep yourself from getting pulled into that person spiral, particularly if it’s someone in your life who is a family member or a domestic partner, where they’re overwork will have consequences for you because you’re having to pick up the slack emotionally or domestically. So sometimes, just setting limits where you’re not going to enable that behavior by papering over.

I think if you hear a person saying, “Well, I have to do this. I can’t do this. Obviously, I need to go to this conference, I need to do this thing.” Gentle questions can sometimes help get them thinking about whether their life is really in alignment with what they value and what brings them happiness.

Again, you have to be careful because I think sometimes people feel really defensive if they’re not ready to have that conversation yet. People are scared, they’re scared that if they give those things up, that they’re not going to be a good person anymore, and so you have to be really gentle and patient with them to come into it on their own terms.

Georgie: Yes.In your book, you talk a lot about how people are also scared to challenge the corporate culture that often exists and perpetuates the way that we behave. I think you give three really useful approaches with regards to overcoming that, which can be applied for anyon. Perhaps you could talk about those.

Devon: Yes. One aspect is really advocating for your autonomy. We know that when people have some control over what their role is, and what their future is in an organization, and they’re not being micromanaged, that’s incredibly motivating. People feel invested in what they’re doing. They feel like they’re getting forward, that they’re actually being respected as a human who can be trusted. Trust really fosters the exact behaviors that deserve trust. It’s kind of an upwards cycle. So trying to tailor your role to the extent that it’s possible to do things that you really actually feel good and rewarded about.

Focusing on the quality of work rather than the hours spent, a lot of workplaces have a culture of busy bragging and just using how often you’re in the office or on-call, and how tired you are as almost a sign of your status, when that isn’t actually a reflection of what you’ve accomplished and what’s important to you and to the role.

A lot of times, if you can do a job really well in three hours, that’s better, certainly for your health and for the organization than trying to squeeze diminishing returns out of yourself productivity-wise by working nine hours or 10 hours.

Then the final thing is really making sure that you’re getting credit for everything that you’re doing. We have so much of our labor and contribution to a workplace undervalued, whether that’s mentoring someone that sits near you informally. We’ve all had to learn new technology this year because of COVID, so we’re developing new digital skills and changing workflow systems on the fly during a really traumatic time. So do not get credit for that, and to be expected to do–

Georgie: And so many other things.

Devon: And so many other things. We’re carrying so much. Then we’re also doing all this technological and logistical work. So making sure that it’s really recognized, here are the skills that I developed this year, here are the workflows that I changed or improved.

A lot of organizations do not have the system set up to recognize when people are doing those kinds of things. So making sure that you really are documenting all of it. This is true in a service industry position too, how many people on the job did you train? How many things are you doing around the kitchen that are not technically your new role, but actually are in your role because if you didn’t do them, the ice cream shop would fall apart? Yes, exactly. So getting credit for those things is also really important.

Georgie: Amazing. Can you tell me why laziness is good? Because that’s a really big part of the book as well. So it’s not just recognizing that it’s a social concept, which is really toxic, but actually embracing it and saying, “No, this is a really good thing to have in our life.”

Devon: Yes, so the idea that laziness is just having a lack of motivation for no good reason, that’s really what I’m talking about when I say, “Laziness doesn’t exist.” People don’t choose to be disappointing, and people don’t choose to fail to meet a goal that they actually care about. If we even think about it for a second, it doesn’t really make sense.

But lazy feelings are lazy in the sense of having a lazy Sunday. Those things are great, and our body is really good at self-regulation, if we learn to reconnect with it and listen to it. If you are zoning out at work, that often means that you need a break, you need more stimulation, you’ve been doing one task for too long, and you need some social contact. Our brains are just not designed to sit and focus on a task for eight hours a day. Basically, no one can do that, and certainly not for the long haul.

So when we’re tired, or we want to just do something that’s a little bit more playful, whether it’s playing a video game, or like playing with our dog, or like going on a walk, those are actually really basic human needs, and those are much of the things that really give life its beauty, and the things that we remember about life being worthwhile.

So instead of seeing those as evil temptations, taking us away from our work, we really need to embrace them and recognize them as our body’s warning system. The more we listen to them, the less we have to worry about being at risk of things like burnout, and some of these illnesses that I experienced and several other people that I profiled in the book went through as well.

Georgie: Yes. Even before that, just not living fully or just being in this state of 70% [unintelligible 00:16:20]

Devon: Yes, we talk a lot about self-care now, but almost always, the public conversation about self-care is just so that you don’t reach the breaking point. It’s just to justify still being productive. Actually, it’s just doing things that feel good to us and help us connect with other people. Those are the reasons why we’re alive.

Georgie: Yes, and that’s how we thrive. It’s how we thrive in work. It’s really interesting talking to a number of the people you’ve spoken to on the podcast now. It gives me hope that corporate culture will start to change because we’ve interviewed musicians, illustrators, great thinkers in this space like yourself, journalists, novelists, and all of them have got it. They know their stuff, that’s how they work. They’ve realized there’s no way they can sit down and churn it out, nine to five. I’m hopeful that this is something that will start to translate because it clearly results in brilliance.

Devon: Yes, we’ve had the data pointing to this for a long time. We just need to look at it in the right way. Industrial-organizational psychologists have known for a really long time that your average worker only can really focus on a task for three or four hours, and the rest of the time we’re at work, if we work a conventional eight-hour day, we’re doing other things. Some of it’s still meaningful work because you’re bonding with other people, but a lot of it’s also just rearranging pens and daydreaming, and that’s just how humans work.

Yes, when you study the life of artists, and just as a writer myself, I can set aside a few hours every morning to write. But if I try to say, “I’m going to write all day long,” it’s never going to actually work like that. I’m just going to be staring at the document after a certain point and just mad at myself because I’ve set a really unfair expectation.

So the answers are there, we can just observe how people actually work instead of the standards that we impose and the expectations we impose. We can see what the answer really is. I do think one of the positives of the pandemic is more and more people are realizing how they actually need to work and live and balance things.

Georgie: I challenged Devon on this because from my perspective, this isn’t always the case. In fact, many people have experienced an erosion of important boundaries, meaning that they feel like they’re working all the time.

Devon: Yes, I think the systems are breaking down. So we see the people who are white-knuckling and just clinging to the old way of doing things and trying to maintain that same level of keeping up appearances and productivity, it’s not sustainable, and more and more people are walking away, quitting industries like law, for example, that are just traditionally very, very grueling. A lot of office workers are just refusing to come back to the office because that commute is just so much time lost of our lives.

I do feel hopeful about that. I’m glad we’re at least in a place where a lot of people are ready to have these conversations, which is great.

Georgie: Devon’s book is incredibly practical when it comes to explaining approaches to reset our lives and to banish the tenant of laziness. They also talk about how, whilst as individuals, we can make changes, we still need to shift the social consciousness around the concept of laziness. I asked him to explain more.

Devon: Yes, I’ve always been underwhelmed by a lot of self-help books because there’s only so much freedom that individual selves have. As you already mentioned earlier, the people who are able to cut back at work tend to be people who have more social status and privilege.

So there are things that I recommend in the book that are practical, just maintaining your sanity and building a life that’s more sustainable for your advice that I do think is relevant to almost everyone. Things like observing your actual habits with a spirit of observation, rather than judgments, and just assuming that whatever you’re currently doing, that’s already your maximum, that you’re already doing the most you could be doing.

So if you want to take something new on, it’s a question of, “What am I doing with my life right now that I’m only doing because I think I should, or because I’m worried about keeping up appearances and seeming virtuous and good? Is there anything I can let go of and reconnect with what my true values are? What do I really prize most in life? What makes me feel alive and fully aligned with my beliefs and principles? And how can I build my life around that?”

At the same time, as much as those steps can really give us a life raft, the system is very broken, and the people who are most rundown by this system are people who are homeless, and aren’t getting benefits and then get blamed for being “Too lazy to get a job.” We need to really push for expanding social supports for people who never will be able to play by the rules of this game that says, “Your life is your productivity.”

Most of us won’t be productive our whole lives. We’ll age, we’ll get sick, we’ll have kids, we’ll have other things going on, so really fighting to create a society where everyone is treated with dignity, no matter their productive capacity, I think is really important for all of us.

I think a lot of times, that can start with just being more charitable to the people around you and when you find yourself wanting to judge someone for relapsing in an addiction, or not being able to find a job, for sleeping all day, thinking about what might be going on with them that is so painful and challenging, whether it’s depression, trauma, systemic racism, whatever it is, usually multiple things, look into that context and keeping that in mind.

Then thinking about, “Okay, how can we really take care of each other, both on a community level and on a more systemic level, so that none of us have to worry anymore about if I get sick, if I can’t make it into work, everything’s going to fall apart?” Because nobody should have to live in that kind of fear. Unfortunately, many do. So yes, that’s how I think about it.

Georgie: This book is part philosophy, part social change, part self-help. It’s cool for compassion is not just about reserving our own judgment, but recognizing that others will continue to judge us based on a social construct of laziness within which they too are embedded. If we continue to live our lives by their standards, we will disappoint. Maybe recognizing that makes life a lot easier.

Devon: Yes, we can let go of other people’s judgment. I really, in my own life, set out to disappoint at least one person a week because I don’t want to measure myself by other people’s expectations anymore. You want to be considerate, of course, but if someone’s demanding too much of you, getting comfortable with being disappointing and living by your own values instead is really powerful. I think it does help free up other people.

Maybe your mom won’t unlearn her relationship to needing things to be tidy, but I think if we all just relax our standards, our standards about presentableness and professionalism and the really arbitrary things that keep a lot of us grinding and keeping up appearances, that frees up everyone else who’s also feeling really stretched thin by that stuff. That, I think, does help change the paradigm.

Georgie: Yes, amazing. Okay, we’re going have to leave it there. Just for me to say, Devon, I’m in awe. I love this book. Thank you so much for being a guest on our podcast today. We’re really, really glad to speak to you.

Devon: Yes, thank you so much.

Georgie: Thank you for joining us on Freedom Matters. If you like what you hear then subscribe on your favorite platform. Until next time, we wish you happy, healthy, and productive days.