Freedom Matters & Anna Lembke: Digital Dopamine 24/7

An addiction expert on why learning to ignore distraction means leaning towards pain

Dr. Anna Lembke is a clinician scholar and a leading global expert in addiction. She recently appeared in the Netflix Documentary, The Social Dilemma, and in August 2021, released the book Dopamine Nation, exploring how to moderate compulsive overconsumption in a dopamine-overloaded world.

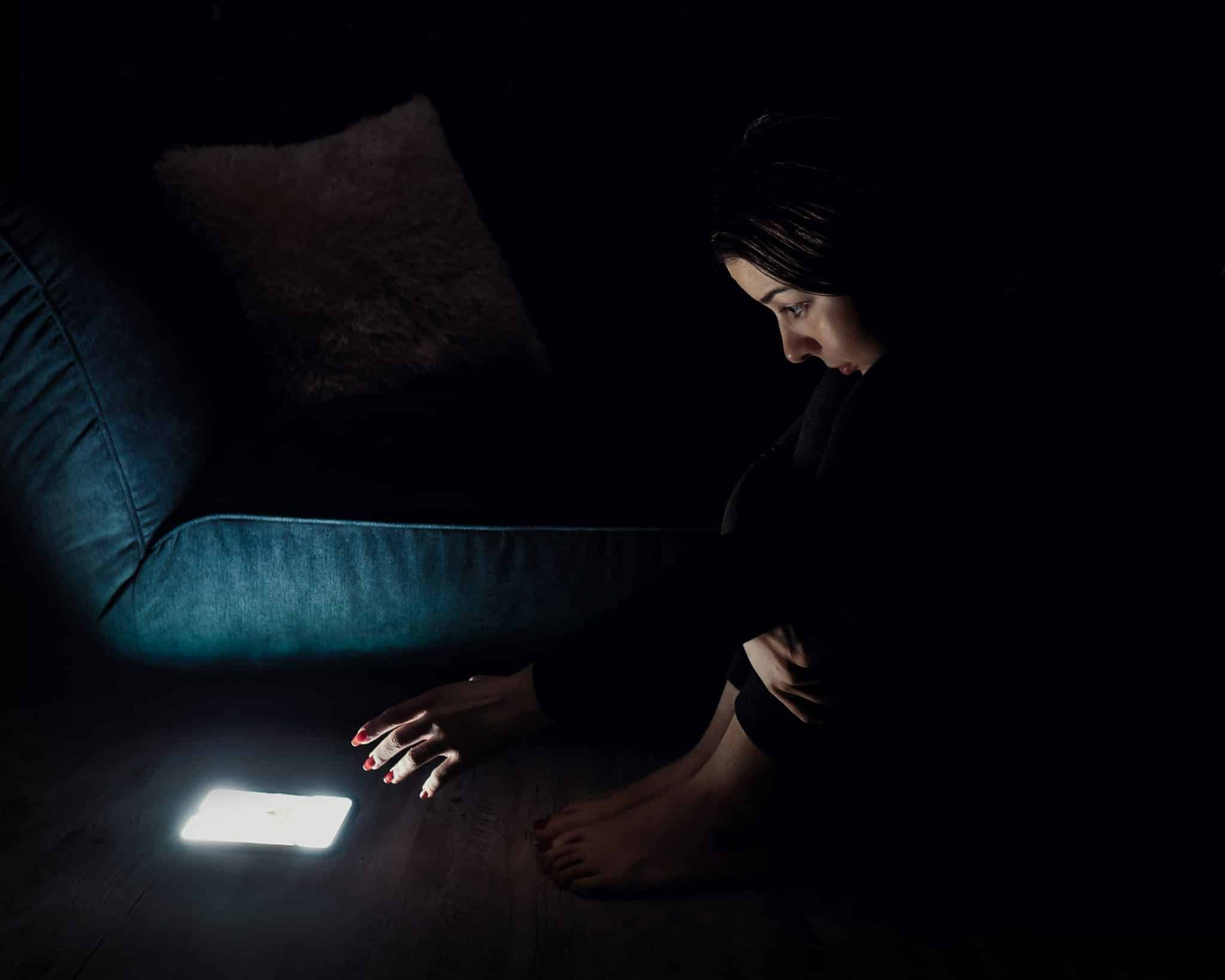

Her view is that, for many of us, our technology use is contributing to our pleasure-seeking habits, tipping our neurological balance and making us miserable. This is an episode rooted in science, which is too important to ignore.

In this episode we discuss:

- Why it is fair and important to use the term ‘digital addiction’

- The role of dopamine on our brains and why it gets us hooked How our ‘tolerance’ to using technology will naturally increase overtime, leaving us wanting more quantity or potency in our digital experiences

- The mechanisms within technology that keep us hooked

- Why it is easier than ever before to get distracted

- Why digital detoxes are necessary

- How to use technology in a more balanced way

- And why, for the sake of our brains, we should ignore distraction and turn towards pain

To learn more about Anna: Anna Lembke, MD – Dopamine Nation

Host and Producer: Georgie Powell Sentient Digital

Music and audio production: Toccare Philip Amalong

Transcript:

Anna: And I really think that if we could do some sort of collective brain scan of modern humans, we would potentially see atrophy of the prefrontal cortex because we’re also used to just having exactly what we want, right away, immediately, the quick answer.

And the result is that the really complicated problems that we face today as a society, problems that will take a lot of collective thought and study, people aren’t willing to put that in. They just want to be outraged, or they just want a quick fix, or, “Why aren’t we just doing this?” or, “It’s your fault.” That’s not going to get us where we need to go.

Georgie: Welcome to Freedom Matters, where we explore the intersection of technology, productivity, and digital well-being. I’m your host, Georgie Powell. And each episode, we’ll be talking to experts in productivity and digital wellness. We’ll be sharing their experiences on how to take back control of technology. We hope you leave feeling inspired. So, let’s get to it.

This week, I’m in conversation with Anna Lembke. Anna is Professor of Psychiatry at Stanford University School of Medicine, and Chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic. A clinician scholar, she has published more than 100 peer-reviewed papers, books, chapters, and commentaries on the topic of addiction.

Dr. Lembke recently appeared on the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma, an unvarnished look at the impact of social media on our lives. And her most recent book, ‘Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence’, has been an instant New York Times bestseller, exploring how to moderate compulsive overconsumption in a dopamine-overloaded world.

Today, we’ll be discussing the neurological pathways of addiction, what heroin and technology have in common, and why we should all turn towards pain.

Anna, thank you so much for joining us today on Freedom Matters podcast. It’s really fantastic to have you as a guest.

Anna: Thank you for inviting me. I’m excited to be here.

Georgie: In her book, Anna discusses how we’ve become addicted to overconsumption. She talks about smartphones as the equivalent of a hypodermic syringe delivering digital dopamine 24/7 for our wired generation.

But her use of the term ‘addiction’ and explaining our relationships with technology is controversial. As we’ve heard from recent guests, this language has been portrayed as disempowering or alarmist. Why is Anna so comfortable raising the flag on how technology is addictive?

Anna: Well, first of all, addiction is a spectrum disorder, as are most mental illnesses. It develops in an iterative fashion over time, and people can be mildly addicted, moderately addicted, severely addicted. Even before mildly addicted, they can be engaging in compulsive overconsumption that could lead to addiction.

Wherever you fit on that spectrum, the same brain processes are being engaged. It’s essentially a hijacking of our age-old motivational system, our reward system. And the vast majority of people who use any drug at all, whether it’s various forms of technology, or whether it’s cannabis or alcohol, will not become addicted to that substance or behavior such that they meet our diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders threshold criteria for addiction.

But nonetheless, the same general process and same reward pathways are being engaged to the point where I believe there’s a lot of homology between severe addiction and, let’s say, destructive habits, or what I call in the book, compulsive overconsumption. So, I think drawing a parallel between those things is valuable. It’s not intended to trivialize severe addiction.

What I do in the book is I hold up people with severe addiction in recovery as modern-day prophets for the rest of us for how to handle this world of overwhelming abundance, this addictagenic drugified world. And I think that’s instructive. I think it’s a useful lens. But at no point am I saying that most people are addicted to technology.

However, I just want to add to that as a footnote that, because there are about 10 to 15% of the population that will get addicted to any readily available drug, we as a society have a responsibility to those individuals as well, even if we’re not in that subgroup.

So, to deny that these digital products have an addictive potential, I think is also wrong, and does a real disservice to the individuals who are vulnerable to that problem. And I see them in my office. I have people with online pornography addiction who are suicidal because they cannot get out of the compulsive vortex of their addiction. I have people who are addicted to video games and who are suicidal and depressed because of that phenomenon.

So, to say that it’s not addictive at all and that people should just buck up and they should have personal agency, yeah, I mean, most people can have personal agency, can see it getting out of control, can make a change, and can course direct. But let me tell you, there’s a subset of individuals who will not be able to do that. And we as a society also have a responsibility to those persons.

Georgie: That’s really important. Thank you so much for making that point. So, can you explain a little bit to us about how dopamine relates to addiction, and also specifically how dopamine relates to the way in which we’re using technology?

Anna: Sure. So, dopamine is a chemical that our brain makes. It’s very important to the experience of reward, pleasure, and motivation. It’s a neurotransmitter. Neurotransmitters are those molecules that bridge the gap between neurons in a space called the synapse and allow those circuits to continue around a neural loop.

So, how does dopamine work in the part of the brain called the reward pathway? Essentially, imagine that in your brain, there’s a balance, like a teeter-totter in the playground. And that balance represents how we process pleasure and pain, which work like opposite sides of the balance.

One of the most interesting findings in neuroscience in the past 50 years is that pleasure and pain are co-located. So, the same parts of the brain that process pleasure, also process pain. And again, they work like a balance.

So, when I do something pleasurable, like eat a piece of chocolate, or look at YouTube videos of American Idol, I get a little release of dopamine in my brain’s reward pathway, my balance tips to the side of pleasure.

But no sooner has that happened, then the brain will adapt to increase dopamine. Because one of the overriding rules governing that balance is that it wants to remain level. It doesn’t want to be tipped for very long to the side of pleasure or pain. And in fact, the definition of stress is any deviation from that level balance, or what neuroscientists call homeostasis.

So, no sooner have I seen a slight increase in my dopamine in response to a stimulus in the environment, or even response to let’s say my memory of a stimulus that I’ve had before because that’s also possible, then my brain starts to downregulate my own dopamine and my own dopamine transmission. But not just to baseline levels. It’s not just like I use up my dopamine and I’m back to baseline, it actually goes below the baseline and puts me in a dopamine deficit state. And that’s craving. That’s that urge to reach for the second piece of chocolate or to watch 1 more YouTube video.

Now, if I wait a few moments, in most cases, that feeling passes, and homeostasis is restored. But if I continue to bombard my dopamine reward pathway with all kinds of pleasures, either the same stimulus or a similar stimulus or another reinforcing stimulus, hence the idea of cross-addiction, I ultimately end up with enough Gremlins on the pain side of my balance to fill this whole room. And now, essentially, I’ve changed my hedonic or my joy setpoint.

And this can take a very long time to correct itself, which is really key for understanding the addicted brain. Because what happens when people get into that state is that now they have this incredible physiologic urge to seek out and use their drug, not to feel good, but just to restore homeostasis and feel normal. In order to feel pleasure, they have to use even more quantities. They have to use more potent forms. Other stuff becomes unpleasurable. So, that’s a key feature of addiction, where we have a very narrow focus on just that 1 type of reward, and the rest of our lives become impoverished.

And here’s a really important point and the last point I’ll make here, is that when we’re not using our substance, our balance is tipped to the side of pain, we’re in a dopamine deficit state. It can last for weeks to months in severe cases. And we’re experiencing in that state the universal symptoms of withdrawal from any addictive substance anxiety, irritability, insomnia, depression, and intrusive thoughts of wanting to use, i.e., cravings.

And that is an incredibly powerful physiologic drive, very hard to resist, which has us seeking out our drug, and which is why we talk about the hijacked brain and why we lose control. Even though subjectively, we feel like, “Oh, I’m just doing this to make myself feel better,” it’s almost an impossible pull to resist because the brain wants to restore homeostasis so badly.

Georgie: Wow. Okay. We don’t normally talk about the product much on this podcast, but we have a pause feature, which basically stops you from being able to access the website instantly. It just gives you that timer to count through. And it’s one of the features that’s most popular amongst a lot of our users. And you can see why.

In her book, Anna explores tolerance and how, over time, exposure to any drug will need to increase if we are to maintain the same response to it. But how does she see this happening with technology? A bit of background here, Anna recently overcame a compulsive behavior herself with romance novels, and she talks more about it here.

Anna: I’ll use myself as an example, and then we can extrapolate to digital products. First of all, my gateway drug was The Twilight Saga, which is a teenage vampire romance series, which was transporting for me for whatever reason. And then that led me to read a whole bunch of other vampire romance novels, and then a whole bunch of other genre romance novels.

But over time, I needed more and more potent forms to get the same effect. So, it’s not just quantity that overcomes tolerance, it’s also potency. And so, I needed more graphic romance novels. And by the end of that sort of cycle that I went through, I was reading 50 Shades of Grey at 3:00 in the morning, which has kind of sadomasochistic scenes with butt plugs and things that I really have zero interest in, but which, over time, that’s what I needed to essentially get the same effect.

And we see that all the time with digital products. So, video games are a great example. People need more and more graphic video games. They need harder levels. Pac-Man obviously is not going to cut it for the modern generation.

We see that with what people are putting out there on Tik Tok and Instagram. Now, all of a sudden, you see somebody do a funny move on a skateboard and fall, okay, that’s interesting. But with more and more videos, now you need somebody to fall and really hurt themselves. Now you need to see somebody jump out a window. Right?

And really, that’s us collectively going through that process of developing tolerance to these visual stimuli. Or intolerance for waiting for things, I think, is evidence of the progression and the changes that we’re individually and collectively experiencing in our brains in this process of becoming more addicted.

Georgie: What element of the technology is the part that’s addictive? Is it the devices themselves? Because I don’t think we talk about that, the devices enough, actually, the sort of the layout, the way they’re curated, the way that they’re designed for consumption rather than creation, the apps and services, and the notifications, or the content and what we’re actually connecting with at the endpoint. Which do you consider to have the most addictive elements?

Anna: So, I think it’s all of that. So, the screens in and of themselves are reinforcing. I had a great conversation with Aza Raskin, who told me a wonderful story about how they were making this supercomputer to solve problems, and they wanted to find ways to distract it. And they tried to find all kinds of different ways.

But it wasn’t until they put a television in the room with a supercomputer that it got really distracted and couldn’t proceed. So, maybe that’s an apocryphal story, I don’t know. But I think it’s a great example of how the screens themselves, they’re like modern-day fires. We’re drawn to them.

But unfortunately, instead of sitting out collectively around a fire and telling stories together, we’re by ourselves in our own room. So, it’s a very isolating experience. I think the tapping and the swiping taps into some kind of primordial urge to do something with our fingers in a repetitive fashion.

The way that they’re engineered, flashing lights, the bottomless bowls, the sense that you can never be done. We all search for ‘doneness’, wanting to feel like, “Okay, I finished that the way.” The we can’t ever get there is part of it. Giving it a number, whether it’s number of likes, whether it’s my ranking, all of that is hugely reinforcing, I think, for reasons that we don’t fully understand.

But when we quantify where we are in the herd, and then we show a visual, simplified graphic image of that, that is really reinforcing. And as you say, then the alerts. Right? The AI learns us. They know what we liked before. And then they suggest to us something similar, but just a little bit different. Again, that novelty piece, that’s a huge trigger for dopamine and reinforcement.

Georgie: It always makes me think, working in business, there’s always this question of are we finding it difficult to find balance with our work, or are we finding it difficult to find balance with technology? Because the work itself can be quite addictive. But the fact that so much of our work now is quantifiable more than ever before, that’s quite interesting in a dynamic itself, I think.

Anna: Yeah. And I think that an important point there is, it’s not just that we now quantify these metrics related to work, but that the metrics are divorced from the meaning of the work itself so that the metric becomes the main thing that we’re seeking. We’re essentially chasing dopamine through the metric, and we lose any sense of what the end product is.

And this is even true in medicine. I’ll get a monthly chart telling me how close I am to my projected billing quota. Am I up? Am I above it? Am I’m below it? And all of a sudden, my patients become objectified in my mind, not as people I’m trying to heal, but as a medium for me to make my numbers. And this is really concerning because it does turn it into a game, divorced from the meaning of the work itself.

Georgie: It’s the sense that, in quantifying more and more, we actually lose more of connections with ourselves and with our own values. And it comes back to a bigger theme within your book, and it’s a theme that’s been coming up in a number of conversations now, how distractions, whether you call it addiction or not, but the fact that we are so easily distracted by technology, and in many cases have developed unhealthy habits with technology comes because it’s a really easy way to avoid pain.

And it seems to me like maybe as society, we’re actually just becoming worse at turning towards these things like boredom, or relationships, which can be hard, or hard, meaningful work. But it’s always been hard to turn towards pain. So, is this new? How is this relationship changing?

Anna: I think what’s different now is the sheer quantity and potency of ways to distract ourselves. This is unprecedented in human history that it’s just that easy to take ourselves away from the present moment and engage with a highly intoxicating substance or behavior that is infinite in quantity. This is really something new.

People have struggled with intemperate intoxicate us since the beginning of human history. There have always been, since the earliest times, reports of people getting addicted to opioids, getting addicted to alcohol. That is not new. What is new is the sheer ease with which we can gain immediate access to those substances and many more that didn’t exist before, including among very young children. Right?

And I really think, as a result, we’re possibly rewiring our brains. There are interesting studies showing that, when people choose from immediate rewards, the part of their brain that lights up most strongly is the emotion part of their brain, or limbic structures, this pleasure-pain balance that I’ve talked about, the reward pathway. When people are choosing from delayed rewards, the part of their brain that lights up is the prefrontal cortex. That’s the part just behind our forehead, engaged in narration, problem-solving, future planning, delayed gratification.

And I really think that, if we could do some sort of collective brain scan of modern humans, we would potentially see atrophy of the prefrontal cortex, because we’re all so used to just having exactly what we want, right away, immediately, the quick answer.

And the result is that the really complicated problems that we face today as a society, problems that will take a lot of collective thought and study, people aren’t willing to put that in. They just want to be outraged, or they just want a quick fix, or, “Why aren’t we just doing this?” or, “It’s your fault?” That’s not going to get us where we need to go.

Georgie: Very interesting indeed. Yeah, it does feel like these harder bits of being human are the things that are most important right now and harder for us to achieve.

Anna: Yeah. And the costs are high. I mean, it’s not just that we’re less happy, because that is the major thesis of dopamine nation, that rising rates of depression that are highest, by the way, in rich nations, depression, anxiety, suicide, all highest in rich nations, I believe that they’re a direct result of our compulsive overconsumption of these feel-good drugs and behaviors.

And it’s not just that we’re feeling worse, we’re also dying. So, 70% of the world’s global deaths are due to modifiable risk factors. The top 3 are smoking, diet, and inactivity. And we are destroying our planet in the process of compulsively overconsuming things that we don’t really need. Our forests, our fisheries, our fuel sources.

So, there’s reason in terms of our own personal happiness to exercise more restraint and to really be thoughtful about this addictive process that I believe we’re all falling prey to. But there’s a very good reason for the purposes of saving our planet and saving the environment.

Georgie: I want to talk about solutions in a minute. But before I do, just 1 quick question. Can addictive tendencies be translated across different types of addictive mediums? Can you move from say, a technology addiction to end up maybe seeking pleasure in another area?

Anna: So, it’s a great question, and it brings up the whole topic of cross addiction. If you take a rat and you get it addicted to cocaine, and that means that rat will press a lever until it dies or is exhausted progressively over time to get that cocaine and sacrifice everything else. And then you take cocaine away for a year, which is a rat lifetime, and then you give that animal unrestricted access to cannabis, it will get addicted to cannabis much more quickly than a rat who had never been exposed to cannabis or cocaine.

So, we do believe that there’s some kind of permanent brain change that occurs once we become addicted to a highly reinforcing substance. And of course, we see that all the time in clinical work, patients who give up 1 drug of choice, only to switch to another, commonly referred to as the whack-a-mole problem.

What’s happening when we develop even these low-grade addictions to social media, or to certain types of food, or to certain types of games or pornography, is that we’re spending more and more time in our limbic brain, less and less time exercising our prefrontal cortex and developing other coping strategies, and learning how to tolerate discomfort, frustration, anxiety.

And so, number 1, not only are we stimulating that reward pathway in a way that, at least for a sustained period of time, will change our brains unless we do something about it, but we’re also not learning other coping strategies.

Georgie: Yeah.

Anna: We’re not spending time figuring out how to be in the world in a different kind of way.

Georgie: Yeah, and that’s really the crux, isn’t it? So interesting. Okay. So, then how to be in that world in this different kind of way, what are your steps? What are the advice you give thinking mainly about people here listening to this podcast who are probably thinking about their relationship with technology and how to find a healthier balance with it?

Anna: My basic approach that I recommend in the book for anybody struggling with any degree of compulsive overconsumption is what I’ve learned works with patients with severe addiction in my clinical practice over the last 20 years.

The first step is a dopamine fast, essentially, a period of abstinence from our drug of choice. I recommend 30 days, because 30 days is the minimum amount of time it takes for homeostasis to be restored, that is for those neuroadaptation Gremlins to hop off the pain side of the balance, and for the balance to be level again for us to upregulate our own dopamine transmission and dopamine production.

And then after that 30-day period, I recommend that folks decide whether or not they want to continue absence or go back to using in moderation. And whether the goal is moderation or abstinence, I suggest what I call self-binding strategies. This is putting metacognitive and physical barriers in place to press the pause button between desire and consumption. So, it’s different from willpower. Willpower is what we exercise after we experienced the desire in an environment where we have ready access.

So, finding strategies are really about changing our immediate environment so that we have a little bit more time or a little bit more space, which is sometimes just enough to allow us to more strategically to harness our willpower or other coping strategies. So, what you talk about in terms of this pause button, that’s brilliant, because sometimes that’s all it takes is just a few extra moments.

So, these self-binding strategies, and I grouped them into 3 major categories, time, space, and categorical meaning. Time is literally pressing the pause button, or just using time as a construct, committing to using only certain days of the week, only certain numbers of hours per day, only after we’ve completed some major milestone.

Space categories are literal geographic barriers, keeping it out of the bedroom, keeping it turned off, keeping it in some kind of safe. When we go to a hotel room, asking them to remove the minibar, remove the television set. So, these are things, again, we do in advance to help us optimize our ability to withstand the pull of desire when we want to do that.

And then the third one is categorical. This is where we say, “You know what? I’m probably okay to watch American Idol YouTube videos, but I’m not okay to watch Dr. Pimple Popper YouTube videos. Because once I start watching those, I’m like off and running and I can’t get myself out of it.”

Or another way to create categorical barriers is to say, “You know what? I’m going to take my drug of choice and make it sacred, something I only use in certain settings, or only on special occasions.” So, first, it starts with a dopamine fast, and then it’s self-binding strategies, whether the goal is then moderation or abstinence.

And let me emphasize that, if the goal is moderation, it is much easier to go from abstinence to moderation than to go from a lot of ingestion to moderation. And you just have to trust me on that, because I’ve seen it so many times in my clinical practice.

Georgie: And it’s a really important point, I think, because digital detoxes are so often criticized. But you’re actually saying, from a medical perspective, neurologically, you need that fast to then think about how to reintegrate it in a moderated way.

Anna: Exactly. And again, if you think about the pleasure-pain balance and dopamine transmission, this dopamine-deficit state that we go into where we really lose our ability to control our response to that intense physiologic urge to restore homeostasis, if we commit to a digital detox, put the barriers in place to make that possible, and then abstain long enough to restore balance, it’s then much easier to go back to using in moderation.

And then the third category of recommendation is actually to lean into pain, to press on the pain side of the balance, to do things that are hard, both physically painful, and emotionally painful. And I suggest a range of different things, from exercise to ice cold water baths, to just reading difficult texts uninterrupted by ourselves or our phones, or whatever it is, to doing things that are anxiety provoking, going out and engaging with people that maybe we don’t really want to engage with, or that prompt our anxiety. To things like committing to telling the truth, not telling a single lie for the whole day.

These are things that are hard to do, but that are really worthwhile that I think upregulate our prefrontal cortical function.

Georgie: Amazing. It sounds big.

Anna: Yeah.

Georgie: I was listening to you today as well on Fresh Air and you’re saying that, on average, people tell 1 to 2 lies a day. And I was trying to think back through my day and think, “What lie have I told today?” And I don’t know, but I’m going to watch myself tomorrow.

Anna: Yeah. I mean, the thing is, we’re usually not aware of it. It’s little things. It’s when we’re late for a meeting and we say, “Oh, gosh, I’m so sorry. Traffic was bad,” when in truth, traffic really was average, but I just wanted a few more minutes to drink my coffee and read a newspaper. That’s the kinds of lies that most of us tell on a regular basis.

But what I argue in my book is something I learned from my patients is that it’s hard, but it’s worth it, because there are many ways in which those incremental lies contribute to compulsive overconsumption, denial, addictive behaviors. Whereas radical truth, telling the truth about things large and small, helps us delay gratification, fosters deep, humane, intimate connections with other people, fosters a plenty mindset over a scarcity mindset, allows us to tell true stories, which is so important not just to framing our past, but also informing future decision making.

Georgie: I’m going to wrap it up there. But before I do, we always ask our guests 1 question, what does productivity mean to you?

Anna: I think, for me, it’s doing the next right thing. So, not reaching for something in the future, but thinking, “How can I make today as good as it can be?” And really trying to stay in that place, echoing a mantra, “Take it one day at a time.” This is an idea that people use to sustain their recovery.

But I think it’s a really good approach to life. Wake up and think, “What is the next right thing that I can do just today? I don’t need to worry about tomorrow. It’s the accumulation of good days that will make a good tomorrow.”

Georgie: Anna, thank you so much for being on the Freedom Matters podcast today.

Anna: You’re very welcome. Yeah.

Georgie: It’s been really fantastic to talk to you. I’m very, very grateful.

Anna: Oh my goodness, my pleasure. Great questions. Great conversation.

Georgie: Thank you for joining us on Freedom Matters. If you like what you hear, then subscribe on your favorite platform. And until next time, we wish you happy, healthy, and productive days.