Working Solo – Rebecca Seal & Freedom Matters

A conversation with the host of The Solo Collective on solitary working

This week we welcome Rebecca Seal. Rebecca is an author, journalist, and occasional TV presenter. Her book, Solo: How To Work Alone (And Not Lose Your Mind) was mostly written in 2019, before the pandemic, but became a bestseller when it was published in 2020. It has now been translated into multiple languages and is available worldwide.

Rebecca also hosts The Solo Collective podcast, a series of conversations about how to cope with solitary working

In this episode, we dive into philosophical and practical advice on how to work ‘solo’.

We cover:

- Why passion for your work can be a problem

- How meaning can be found in all forms of work and life

- The money trap

- How to work solo but never alone

- Resilience for solo workers

- How to fuel your body for work

This episode is part of our mini-series on the Future of Work. Listen to episodes with Chase Warrington, Alex Pang and Shamsi Iqbal to hear more.

Host and Producer: Georgie Powell Sentient Digital

Music and audio production: Toccare Philip Amalong

Transcript:

Rebecca Seal: And the idea that you’ve got to find your passion and get someone to pay you for it. I mean, that’s literally what was written in a little notebook that I was given when I was a kid, “Do what you love, and you’ll never have to work a day in your life.” And actually, I quite honestly think that’s bollocks, because you don’t have to love your work.

Georgie Powell: Welcome to Freedom Matters where we explore the intersection of technology, productivity, and digital wellbeing. I’m your host, Georgie Powell, and each episode we’ll be talking to experts in productivity and digital wellness. We’ll be sharing their experiences on how to take back control of technology. We hope you leave feeling inspired. So, let’s get to it.

This week, we welcome Rebecca Seal, author, journalist and occasional TV presenter. Her book, ‘Solo: How to Work Alone (and Not Lose Your Mind)’, was mostly written in 2019 before the pandemic, but became a best seller when it was published in 2020. She is the host of Solo Collective podcast, a series of conversations about how to cope with solitary working, and is also an award winning food and drink writer, and has written 10 cookbooks, most recently, ‘Leon’s Happy Guts’, a cookbook about good gut health. Today, we’ll be talking all about how to work solo. We’ll be discussing whether work should have meaning, how to avoid loneliness, and how to fuel your body for work.

Rebecca, welcome to the Freedom Matters podcast. Thank you so much for joining us today.

Rebecca Seal: Thank you for having me. It’s great to be here.

Georgie Powell: So, we’re just having a little preamble and we’re talking about how your book reads really wide ranging covering philosophical thoughts, as well as very practical thoughts about how to work better as a solo worker, which so many of us now are. And one of the things that stuck out for me was this whole chapter you’ve got around meaning and purpose and passion. Love that word, ‘passion’, really why we do our work. I’d love to get your thoughts on why you decided to include that in your book, and why you think it’s such an important thing to discuss as solo workers.

Rebecca Seal: Because I think we get in a bit of a tangle about all of it. I think, on the one hand, we feel like our work has to be meaningful. Like we’re taught that work should be meaningful and purpose driven, and you should have a passion for it. And I have a real problem with that. Because I don’t think that that is possible for most of us, nor healthy for probably all of us.

And so, I wanted to discuss that and just ask some questions for people for readers to think about in terms of, do we really need our work to be meaningful? Can we find meaning in other places? Is being forced in a way to think about work as meaningful, a way for people to exploit us?

There’s really good data to show that, that people who are considered to be passionate about their work are more likely to be exploited, more likely to be given tasks outside their explicit role and are more likely to be forced to work longer hours. And then once I’d read that study, I was quite worried about this passion idea, and the idea that you’ve got to find your passion and get someone to pay for it.

I mean, that’s literally what was written in a little notebook that I was given when I was a kid, “Do what you love, and you’ll never have to work a day in your life?” And actually, I quite honestly think that’s bollocks because you don’t have to love your work. I would say that I really liked my work, and I’m really lucky to do the job that I do. But it’s not my passion. And I’m not sure I have a passion. And I’m not sure I’ve got the energy for a passion. I’ve got a partner. I’ve got 2 small kids. I’m a daughter. I’m a sister. I’m a friend. There’s a lot of other stuff in my life that deserves my kind of undying attention. And I’m not sure that work is one of those things.

Georgie Powell: Yeah.

Rebecca Seal: And that’s not true for everybody. Some people feel really strongly about their work. And like, don’t get me wrong, I want to do my job really well, and I do really care about it. But I don’t want to be consumed by it. And I’m not sure that being consumed by your job is necessarily something to be ambitious towards. And also, it came about because part of my job is as a food writer, and I spent a lot of time working with chefs in a decade or something. And I just saw this kind of cycle of passion, overwork, burnout, and really chaotic personal lives appear over and over again. I couldn’t help but feel that it was fundamentally tied to this idea of passion.

And I just began to think, “I think we’ve got a problem.” This section in the book is called The Passion Problem, because I think it really has the capacity to be damaging. And it’s new to it’s not how we thought about work 200, 300 years ago. We weren’t encouraged to think of being passionate about like being an agricultural laborer or weaving on a loom. And those people that had the opportunity to do jobs, which they were, quote, ‘passionate about’, and they wouldn’t have described it that way, it was so rare.

It’s not necessarily that I would say having a passion for your job is definitively bad. But I do think it’s a conversation that we should have a bit more clearly.

Georgie Powell: And I feel that your perspective is really different to the way that, I’m going to move back into kind of like company culture now away from solo culture, but actually more and more companies trying to really push up the values of their business, the impact that they’re having. And then you’re saying, “Hang on a minute, I actually don’t think this is a good way for us to be going.”

Rebecca Seal: Yeah, I agree. I saw a funny thing on I think it was on Twitter a few days ago, where someone said, “Red flag, if a company says that they treat you like family, know that that means they’re going to screw you up psychologically.” And I think that really encapsulates the whole issue, right? You don’t actually want to be so deeply involved with your work that you are emotionally tied and affected to it and by it. You want to have a degree of separation from your personality and your work.

And I think, again, I go on about this in the book quite a lot, I think I say it 4 or 5 times, we have this linguistic problem, particularly in English, when we talk about our work. We say, “I am a…” Our job becomes an extension, or indeed the whole of our personality. And when I was talking about leaving my job as an assistant editor at the Observer in order to go freelance, which I ultimately did, but it took me like half a year to make the decision, because I had this such strong attachment to the idea of being a thing, that I couldn’t really think of who I would be without that.

And again, that’s not true for everybody. Some people have slightly healthier psychological setups than I did at that time in my life. But it’s a really difficult thing about the way that we work now, is that we make it such an enormous part of who we are and how we live. And that’s great if it’s going well, but it won’t go well for the whole of our careers. It cannot, it does not for everybody. And then that can become incredibly painful, as well as the whole question of burning out just through over overwork and overzealous attachment to our jobs.

Georgie Powell: Yeah, because your job comes down, and because your identity is so linked with your job. But in your book, you do say that finding meaning is important. And you can create more meaning in your work as well. So, it’s kind of a fine balance, right?

Rebecca Seal: Yeah, it’s a really fine balance. I think it’s important to think of ways of peeling away the onion of sort of social and cultural expectations. So, if you say to someone, “What’s a meaningful job?” they’ll say, “Nurse, doctor, nongovernmental aid worker,” or whatever. There’s a very specific list of meaningful jobs. But actually, the question is not what is a meaningful job in the kind of objective sense, but what is subjectively meaningful to you?

It’s about asking questions of why you’re doing your work, and if it’s what you specifically want, rather than what you feel is expected of you, or what culturally we’re told is meaningful. It’s about having this kind of internal dialogue that I don’t think we’re taught to do as teenagers when we’re trying to decide what we’re going to do with our lives, which terrible time to make any decisions, let alone that one.

And we’re not taught it as we go through our 20s. We’re just put on a career track with very obvious steps on it. And it’s quite difficult to think about, “Am I doing this for me? Am I doing this for money? Am I doing it because it feels like it’s got real purpose and meaning for me specifically?” I don’t think we’re socially very good at doing that.

Georgie Powell: So, your book, as I said before, it’s really wide-ranging, it’s shots between philosophical points, and then quite practical points. And seeing as you just brought it up, I think we’re going to jump to the money trap. Can you explain what you talk about in terms of the money trap? I think it’s really, really important for our listeners to hear.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah, money is a really complicated one. It does some really weird stuff to our brains. So, I think one of the things that I was most fascinated to learn about was the idea that when you start placing a monetary value on units of your time, it makes your time as a whole feel more scarce. So, if you’ve got like a day rate, which many of us do, then the simple act of putting that rate on your time can make your time feel more frantic and more frenzied, and more scarce.

And scarcity in itself also has a really interesting impact on the brain. There’s a really brilliant book called ‘Scarcity’, which I recommend everybody read, is about the kind of economics of scarcity, but also the impact of scarcity on the on the brain’s bandwidth. It seems as though the more we think about money, and the more we put value on our time, like a financial value on our time, the more it can feel like we don’t have enough time, basically, which is a sort of frenzied feeling that so many of us feel a lot. So, I think that’s one of the traps.

The other trap is that the way we value our time can affect our happiness. So, there’s a short longitudinal study that was done with students and those who valued their time more than their income were happier in the years following their graduation than those who felt in the opposite direction. Ashley Whillans is a really brilliant person to look up. She’s written some amazing stuff for the Harvard Business Review on exactly this.

But essentially, the message is, value your time more than your money. And if you can spend your money on getting more time, or on experiences rather than stuff. Because those are the things which bring joy and happiness, both in the short and long term. And yet, so many of us focus really strongly on earning more and more and more.

And I put myself very much in that bracket up until really quite recently. Because especially if you work for yourself, but I think it’s also true in loads of other ways of working, we’re so bad at judging our own success that we use money as the metric. And if you’re freelance, that’s particularly true.

So, I didn’t really have any other metrics. I hadn’t had a conversation with myself before I started working on ‘Solo’, which I should say, I came to write because I was completely miserable and burned out and had been working on my own for 6 years, and basically hadn’t thought about how to do it at all. I just put my head down as soon as I went freelance and worked and worked and just tried to earn as much as possible.

And I just didn’t have another way of judging whether things were going well or badly, I could just only have my bank account, because I haven’t given myself any other ways. And I think that, again, that’s true for so many people, people just don’t know how to value what they’re doing, apart from whether it’s earning them X amount, or more than last year, or whatever.

And so, that’s another part of the trap, I don’t have a problem with people wanting to earn more or wanting to get up for their career ladder, whatever their ladder might be, the only thing I have a problem with is the kind of blindness with which some of us do it. It’s completely legitimate to say, “I’d like to earn more than I’m earning,” and legitimate today, “And I want to succeed in X or Y way.” The problem is just that we do it without figuring out what means something to us and what doesn’t.

And I’m much happier now that I have created a whole set of metrics. We have the same conversations about like, “Who’s earning?” and, “Are we earning enough?” and all that kind of thing. Those are all important conversations to have. But I also have conversations with myself about whether the work is the work I want to be doing, whether it’s giving me value, whether it’s giving me satisfaction, all that stuff. And that was what I was lacking before.

Georgie Powell: And in terms of spending money to support yourself and getting more time back, one of the things I love kind of really early on as you introduced concept, you think we’re working alone, but actually we’re not. We’re all still working as part of teams. And I’d love you to talk a little about that and explain how teams are around us all the time, we just have to be aware of them.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah. You really need to kind of defend yourself from loneliness and isolation. And being aware of your team is a brilliant way of doing that. So, my team is such a middle-class, middle-aged team to have, but my team includes the people who do childcare for my children. So, it’s like the after-school club staff and ad hoc nanny that we use occasionally, friends who babysit, my parents who help us, my in laws who help us. It’s also the cleaner that we have to clean our house and the studio business that we run. It’s the person who helps with my transcription. It’s the person who does my husband’s invoicing. It’s a whole mess of people.

Georgie Powell: Yeah.

Rebecca Seal: And I’m really grateful for all of them and I’m really aware of all of them. But I probably don’t see, especially now but even before the pandemic, I probably didn’t see any of them more than like once a year. I mean, obviously, I see the people who give my kids childcare, but the people who do transcription or invoicing or whatever, that’s a much more distant connection. But they’re still really important.

And the other part of it is that by using other people’s businesses, you’re allowing other people’s businesses to grow and survive. And I think that we have this awkwardness, particularly in the UK about paying for help. I think we need to get away from that a bit and say, “It’s fine to ask for help and to pay for help.” All the help that you can get, all the outsourcing that you can do as soon as you can afford to do it is really valuable. If you can spend money to gain time, then that’s a great thing. But you’re also creating a web of community around yourself and supporting other people’s businesses. So, I don’t feel like any of that is bad.

Georgie Powell: And you’re taking away a sense of isolation, which can be so crippling.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah, yeah.

Georgie Powell: And yeah, actually creating a crew.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah, exactly. You need a crew. Even if this doesn’t involve any kind of financial exchange, it’s really worth creating a kind of set of virtual colleagues, have relationships with people who are really supportive of you and what you do, even if they don’t exactly know what you do.

One of the things that I found really amazing recently in the last year, I’ve started to share an office with somebody who works in the charitable sector in education. And we don’t know anything about what each other do, but it’s been brilliant having somebody outside of what I do to talk to. And she has amazing ideas, and I have really good ideas for her too. So, I think, yeah, that’s been really eye opening and really valuable.

Georgie Powell: Whether you’re feeling very busy, or managing your time so that you don’t feel too busy, it can be hard to carve out the space for networking. I asked Rebecca how she found the time.

Rebecca Seal: If anyone else is at the beginning, just don’t do what I did. Don’t be lonely. And don’t be territorial with your time and with your expertise, because it doesn’t mean that you get more done. You just spent more time feeling really lonely and staring at a wall. So, do as I say, not as I did.

Georgie Powell: This is not good. Don’t do that.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah.

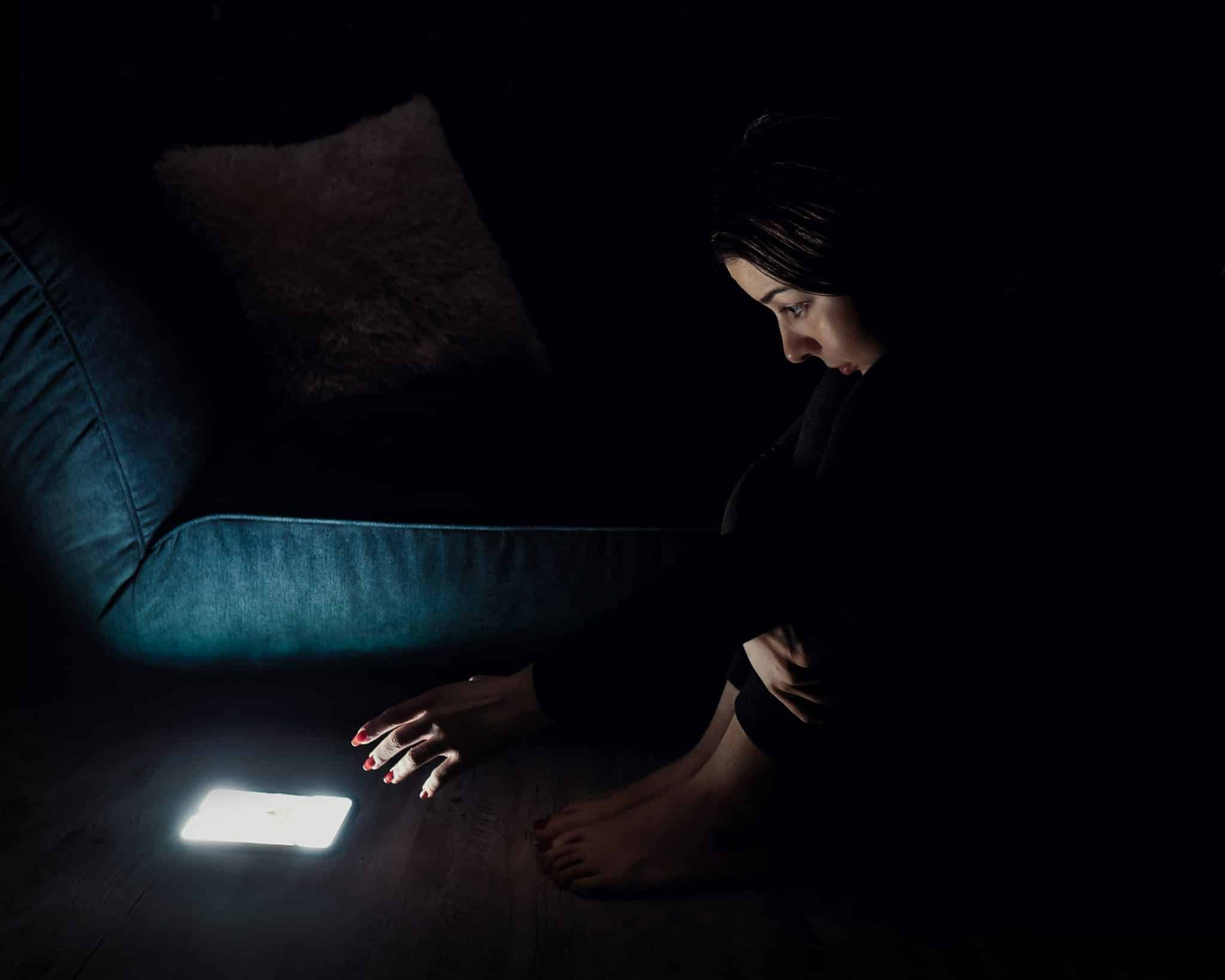

Georgie Powell: Okay. And it does bring us on to this other philosophical point, which is, I find really interesting with your section on courage and resilience. And you talk about how you basically have to build resilience, you have to learn how to do that, you have to get pretty good at it, especially if you’re working on your own. One of the things we talk about quite a lot is the role of tech on how resilient we are. And the problem with it is it’s kind of amazing escape mechanism, which means that we don’t turn to these difficult things head on, we’ve got distraction mechanism all the time. And it’s really easy to run and hide.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah.

Georgie Powell: Whereas what you’re saying, and what so many people who have specifically formed better habits with tech say, is that you just have to turn towards pain. If you’re going to get anything meaningful done, if you’re going to get into flow, if you’re going to feel like you’re really making progress in life, you have to face it head on. You’re kind of coming at it from a different angle, but I think the message is the same.

Rebecca Seal: I think tech is good-ish. But I feel as though the more I learned, the more I think that the distraction situation is a really dangerous one. I mean, it’s like smoking used to be, right? You never have to sit in a bar or on your own looking at the wall or the ceiling, because you’ve always got something to do. And now it’s like it totally acceptable for everybody to do the technical equivalent, which is scrolling. I think that’s really problematic.

I do think that standing and facing is the kind of the way of building resilience. I also think that just to go back to our point about creating networks. For something I’ve read more recently after I wrote the book, Bruce Daisley has just finished writing a book about resilience called ‘Fortitude’. And I’ve talked to him about it quite a lot. And he writes about how resilience is social strength. Resilience comes through community. And being resilient sort of independently, anything or anyone else is impossible.

And so, I think, on the one hand, you do have to do it. But on the other hand, you need to do it collectively. We have to do resilience, as it were, collectively. And it’s a muscle that we can strengthen. It’s not something that you either have. It’s not binary, you don’t have it or not have it.

But I’m hopeful that after the experience of the last couple of years that we will find levels of community resilience and individual resilience that we didn’t know that we had in a kind of whatever the modern version of the Blitz spirit would be. I know it doesn’t feel like that in terms of how communities feel at the moment. But I think there’s precedent for things to improve.

Georgie Powell: In the book, you said your hope that the smaller irritants will grind us down less, and perhaps it will be easy to do the harder things post pandemic. I’m really glad you’re optimistic about it. I feel like we’re still in it, aren’t we? It’s too early to say.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah.

Georgie Powell: Like, I just sit around, I feel everyone’s exhausted and actually probably more down than ever.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah, yeah. And when I wrote that, I wasn’t expecting it to go on for 2 years. I wrote that in the first 6 weeks of the pandemic.

Georgie Powell: Yeah. We were all so optimistic then, weren’t we? It’s like, “Oh, the sky is clear. There’s no traffic. The earth is breathing again.” But yeah, it did go on a lot longer than we expected.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah, it’s true. But I also think, again, there’s precedent.

One of the people I interviewed was talking about how she very often gets called by communities who’ve experienced disaster. So, she specializes in disaster recovery. And she often gets called by communities who have experienced a more sort of traditional disaster, like a tornado or an earthquake. And they have this kind of window of time directly after whatever it’s happened, where everybody comes together, and there’s a sort of sense of community cohesion.

And then as the aftermath of the disaster drags on, as they inevitably do, then you get fracturing. You get this kind of real anger and unresolved conflicts. And that’s when they come to her. And we are in that phase. And that phase is one which will end. It’s not wanting to be ignored.

Georgie Powell: Yeah.

Rebecca Seal: We need to try and do stuff to get through it. But one of the big parts of getting through it that the advice that she gives to communities who are struggling is to come together to do things together. And obviously that’s been incredibly challenging because of parts of the endemic isolating us so much.

So, again, it comes down to, wherever you possibly can, re-ignite your social connections. And that can be as simple as going to a coffee shop, getting a coffee or having a chat with the barista, or talking to other people in the line, or making eye contact with other people, or just like eating where you can leaving your house. Or going to an outdoor concert, or buying your paper clips from a real shop rather than online.

Georgie Powell: Yeah.

Rebecca Seal: All of these small steps that we can take where we’re around other people. Because all of this experience has robbed us of empathy. It’s robbed us of connection. The experience of the pandemic has literally downgraded our ability to be empathetic.

I interviewed a psychologist, Brandon Court, and he was fascinating on this, but it affects us cognitively, to the degree that our empathetic abilities are starting to disintegrate. And that’s really important when you work by yourself or indeed when you work at all. But it’s really important, because if we’re angered and fearful of the other, then we become progressively more isolated and progressively more angry and fearful. And the whole thing spirals out of control.

And we can see that across society, but it’s also affecting us very much as individuals. And when you’re solitary in work, you have to fight against that stuff, even harder than people who are part of big organizations and big teams where they actually see other humans.

Georgie Powell: Well, I’m glad you’re optimistic though. So, we’ll get out there. We’ll start smiling at dog walkers and yeah, grabbing coffee.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah, exactly. All of that stuff. Yeah, yeah. I mean, it really is. Like, do, get out. Go and look at… and I mean, I always say this. People say, “What’s the piece of advice that you most give to people?” and I always say, “Go and look at a tree. Like, get out away from your screens and your digital distractions and go and look at a tree. Like, there are measurable health benefits to that.” It’s not going to solve all the problems.

Georgie Powell: Yeah.

Rebecca Seal: It’s not going to solve all the problems. It’s not a mental health panacea. But it will help.

Being on our own alone in gloomy indoor rooms, and we’re recording this in January, it’s very gray. That stuff doesn’t help. It builds up to encourage our well-being to fall apart.

Georgie Powell: Very good. And then I think the last kind of really practical bit in your book as well is around… well, there’s lots of other practical bits, but that stood out for me as well is about food, which again, very practically is bolstering us every day and make sure we eat and drink the right stuff when we’re working from home working on our own, which so many of us forget to do. Toast is not a meal.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah, yeah, guys, it’s really not. Sorry.

Georgie Powell: Peanut butter?

Rebecca Seal: A good source of vitamin B 12, maybe peanut butter. The thing is, I don’t want to sound like I’m judging anybody’s food choices. I think the moralization of food is a really big problem separate to all of this and a whole other podcast topic. So, don’t take this to mean that I’m sort of telling anybody off. But the way that we feed ourselves is the way that we show ourselves love. And we all need love right now more than ever.

But it’s also how we fuel our brains and fuel our bodies. And having a decent lunch is a really great way of not eating a packet of hobnobs in the afternoon, which was always my big downfall.

Georgie Powell: Salted hobnobs.

Rebecca Seal: Yeah, oh yeah.

Georgie Powell: They dunk in [inaudible].

Rebecca Seal: Yeah. But it’s never just 1, right?

Georgie Powell: Never just 1. Like, I wrote that chapter, and I think I’d eaten 5 hobnobs that morning, and I think I put that in the chapter. So, obviously, I fall off the wagon all the time. I’m definitely not perfect. But I had so many conversations. I went into Facebook groups, and I talked to people in real life who work on their own. And so many of the people in the conversations would say to me, “What do I eat? How do I not eat everything in the fridge? How I not eat nothing? How do I not just stand looking at the fridge eating fromage frais destined for a child while looking at my emails?”

I was really surprised, because I didn’t think that that was going to be one of the big issues that people were struggling with. But it turned out that it really, really is. And I think part of it is about the kind of broader philosophy of how you feel about yourself and your work, in that we’re not very good at putting ourselves at the top of the pile. And we’re also not necessarily that good of putting our work at the top of the pile.

So, if you’ve got a caring role, or you’re a parent, or you’re in a family setup, or I mean, there’s so many ways in which work can get squashed. And when I’m talking about meaning earlier, I was saying how we shouldn’t let the work that we do be the biggest part of our personality. But it’s also important that, in the moment when you’re supposed to be working, you do prioritize work, like not prioritized laundry or whatever other jobs and roles you could be taking on.

And part of that philosophy is about saying, “I will fuel my work enough. I will take time away from my work to fuel it, and my brain and my body and to look after myself enough that I can do this role that I’m going to do for the next 2 hours or 4 hours or 8 hours or whatever it may be.”

And when we constantly squash our work into little tiny windows of time, or when we think of ourselves as not having done enough work, or not being worth of stopping because we should be working harder and guilt and all of that stuff, it makes it really difficult to take breaks. But breaks are what make us really good at the work that we do. So, it’s really important to invest in them, and particularly in fueling yourself with really nice meals.

So, basically, the message is just to have a lunch break. Have something decent like some nice soup, or an egg or something that’s quite filling, and that’s quite loving towards yourself. And then the work that you do in the afternoon will be easier and quicker, and you will be able to finish it at whatever your cutoff time is and go and get on with the rest of your day.

Georgie Powell: Sounds great. Perfect. Okay. Well, on that note, I’m going to just say, Rebecca, you’ve been a fantastic guest on the Freedom Matters podcast. Thank you so much for joining us today. It’s been a delightful way to start the day.

Rebecca Seal: Thank you for having me. And I’m really grateful for this conversation. I’m really grateful that people are having these conversations because I think this stuff really, really matters.

Georgie Powell: Thank you for joining us on Freedom Matters. If you like what you hear, then subscribe on your favorite platform. And until next time, we wish you happy, healthy and productive days.